The Learning Paradox: Stateless Systems Cannot Improve

The promise of artificial intelligence agents is that they will handle consequential tasks autonomously—approving loans, managing portfolios, optimizing supply chains, moderating content. Yet beneath this vision lies a hidden paradox: most AI agent architectures are fundamentally incapable of genuine learning. They process information, make decisions, and then forget. When the next task arrives, they begin again from zero. They cannot accumulate wisdom from past experiences. They cannot refine their judgment through repeated exposure to similar situations. They cannot develop expertise. In essence, they are perpetually novice systems, regardless of how many tasks they have completed.

This architectural limitation exists by design. Large language models are stateless. Each inference is independent. Each prompt is processed as if it were the first prompt ever written to the system. The system has no way to modify its internal weights based on experience. It cannot retrain itself. It cannot adjust its behavior based on outcomes.

The traditional workaround is external logging: save decision histories to a database, then at some future date, retrain the entire model with all that accumulated data. But retraining is expensive, time-consuming, and typically happens monthly or quarterly at best, not continuously. Agents cannot learn in real-time. They cannot self-improve through interaction.

Vanar fundamentally rethinks this problem by asking: what if the blockchain itself became the infrastructure through which agents learn and remember? Not as a secondary logging system where decisions are recorded after the fact, but as the primary substrate where memory persists, reasoning happens, and learning compounds over time.

Neutron: Transforming Experience Into Queryable Memory

At the core of agent learning is the ability to retain and access relevant prior experience. Neutron solves this through semantic compression. Every interaction an agent has—every decision made, every outcome observed, every insight generated—can be compressed into a Seed and stored immutably on-chain. Unlike databases where historical data sits passively, Neutron Seeds are queryable knowledge objects that agents can consult directly.

Consider a lending agent that processes a mortgage application. In a traditional system, the decision and outcome might be logged to a database. But the next time the agent encounters a similar applicant, it has no way to access that prior case. It does not know that last quarter, three hundred applicants with similar profiles were approved, and one hundred of them defaulted. It cannot answer the question: "Given this borrower's characteristics, what was the historical default rate?" It starts fresh, applying the same rules it has always applied.

With Neutron, the lending agent stores the entire context of that decision as a Seed: the applicant's financial profile, the underwriting analysis, the decision made, and crucially, the outcome six months later. When the next similar applicant arrives, the agent queries Kayon against Seeds of comparable past cases. "What happened to the last ten applicants with this income-to-debt ratio? How many paid back their loans? What distinguished the defaults from the successes?" The agent's decisions become increasingly informed by its own accumulated experience. It learns.

The compression is essential because it makes memory efficient and verifiable. A thousand mortgage applications compressed into Seeds occupy minimal blockchain space—far less than storing raw files. Yet the compressed Seeds retain semantic meaning. An agent can query them, analyze them, and learn from them. The Seed is not a black box; it is a queryable knowledge object that preserves what matters while eliminating redundancy.

Kayon: Reasoning That Learns From Memory

Memory without reasoning is just storage. Kayon completes the picture by enabling agents to reason about accumulated experience. Kayon supports natural language queries that agents can use to analyze their own history: "What patterns emerge when I examine the last thousand decisions I made? Which decisions succeeded? Which ones failed? What distinguished them?"

This capability transforms the agent's relationship to its own experience. In traditional systems, an agent might make a decision and later learn it was wrong. But there is no automated way for it to adjust its behavior based on that outcome. The adjustment requires human intervention—retraining on new data. With Kayon, an agent can continuously interrogate its own history, extracting lessons without retraining.

A content moderation agent might use Kayon to analyze patterns in its flagging decisions: "Of the thousand comments I flagged as hate speech, how many did human reviewers agree with? For the ones they disagreed with, what linguistic patterns did I misidentify? How should I adjust my confidence thresholds?" The agent is not retraining in the machine learning sense; it is reasoning about its own track record and self-correcting through logic rather than parameter adjustment.

This distinction matters. Retraining requires massive computational resources and occurs infrequently. Reasoning happens in real-time. An agent can correct itself between decisions. It can refine its judgment continuously. For high-stakes applications where the cost of error is measured in billions of dollars or millions of lives, this difference is profound.

Emergent Institutional Memory

The most transformative aspect of Vanar's agent architecture emerges when organizations deploy multiple agents that share access to the same Neutron and Kayon infrastructure. Each agent learns independently, but all agents can benefit from all accumulated organizational knowledge.

Imagine a bank with five hundred loan officers being replaced by fifty lending agents. Each agent processes one hundred loan applications per quarter. That is fifty thousand lending decisions annually. In a traditional system, each agent makes decisions based on rules, and there is limited cross-pollination of insights. If agent one discovers a novel risk pattern, agent two does not know about it unless a human explicitly transfers the knowledge.

With Neutron and Kayon, every decision made by every agent is immediately part of the shared institutional knowledge. When agent two encounters a situation similar to something agent one processed, it can query the Kayon reasoning engine against agent one's past decisions. All fifty agents are learning from the same fifty thousand examples. The institutional knowledge is not fragmented; it is unified and continuously growing.

Over time, this creates what might be called emergent intelligence. No individual agent is retrained, yet collectively they become increasingly sophisticated. Patterns that no human analyst explicitly coded emerge from the accumulated experience of the agent fleet. Risk factors that statistical models never detected become apparent through Kayon analysis of millions of decisions. The organization's decision-making becomes smarter not through algorithm changes, but through accumulated wisdom stored as queryable Neutron Seeds.

Learning That Persists Across Agent Generations

Another crucial implication: when an agent becomes deprecated, its accumulated learning does not vanish. The Neutron Seeds created during its operation remain on-chain. When a successor agent is deployed, it inherits the full institutional knowledge of its predecessor. The organization does not start learning from scratch with each new agent version. It begins with everything that prior agents discovered.

This is categorically different from how institutional knowledge currently works. When an experienced human leaves an organization, their expertise often leaves with them. When a team reorganizes, informal knowledge networks are broken. When software systems are replaced, documentation is discarded or becomes inaccessible. Vanar makes institutional knowledge permanent and transferable. It becomes a property of the organization rather than an attribute of individual agents.

For sectors where expertise is difficult to codify—medicine, law, finance—this represents a fundamental shift. A medical decision-support agent that learned how to diagnose rare conditions across millions of cases transfers that knowledge entirely to its successor. A legal research agent that absorbed case precedents does not erase that learning when a new version deploys. The organization's collective intelligence compounds with each agent generation.

Self-Reflection and Calibration

Beyond simple memory retrieval, Vanar enables agents to engage in self-reflection. An agent can ask Kayon to analyze its own historical accuracy: "When I expressed high confidence in a decision, how often was I right? When I expressed doubt, how often was I wrong? How should I calibrate my confidence thresholds based on actual performance?" This is epistemic self-improvement—the agent learning not just what to decide, but how confident it should be in each decision.

For regulated industries, confidence calibration is essential. A lending agent that claims ninety percent confidence in its loan approvals had better be right ninety percent of the time. An insurance agent that denies claims with eighty percent stated confidence should rarely be proven wrong. Vanar enables agents to continuously verify and adjust their confidence levels based on empirical outcomes. The agent is not guessing; it is calibrating against reality.

This feedback loop, when systematic, creates agents that improve dramatically over time. Early in deployment, an agent might be overconfident or underconfident. But through continuous self-reflection against Neutron-stored outcomes and Kayon-enabled reasoning, it refines itself. The agent that started with seventy percent accuracy can reach ninety-five percent accuracy—not through retraining, but through accumulated self-knowledge.

Accountability Through Transparency

A consequence of agents learning from queryable memory is that their learning is fully auditable. When a regulator asks why an agent made a particular decision, the answer is not "the machine learning model decided"—an explanation that satisfies no one. The answer is "I examined similar cases in my memory. Cases with these characteristics had an eighty-five percent success rate. Cases with that characteristic had forty-two percent success. Based on this aggregated experience, I assessed the probability at sixty-three percent."

This transparency is not incidental; it is fundamental to Vanar's architecture. Because reasoning happens in Kayon and memory persists in Neutron, both are auditable. The agent's decision trail is verifiable. The data it consulted can be inspected. The logic it applied can be reproduced. No black box. No inscrutable neural network weights. Just explicit reasoning based on queryable evidence.

For institutions that need to explain decisions to regulators, customers, or courts, this capability is revolutionary. It removes the core objection to autonomous agents in high-stakes domains: the inability to justify decisions in human-understandable terms. An agent running on Vanar does not have that problem. Its decisions are justified by explicit memory and deterministic reasoning.

The Agent That Knows Itself

Ultimately, what Vanar enables is something unprecedented: agents that actually know themselves. They understand their own track record. They learn from their own experiences. They improve over time. They can explain their reasoning. They become wiser, not just faster.

This stands in stark contrast to current AI systems, which are fundamentally amnesic. ChatGPT does not remember you after you close the tab. A language model fine-tuned for a task does not improve through use; it remains fixed until someone explicitly retrains it. Current AI agents are sophisticated pattern-matchers that reset with each new interaction.

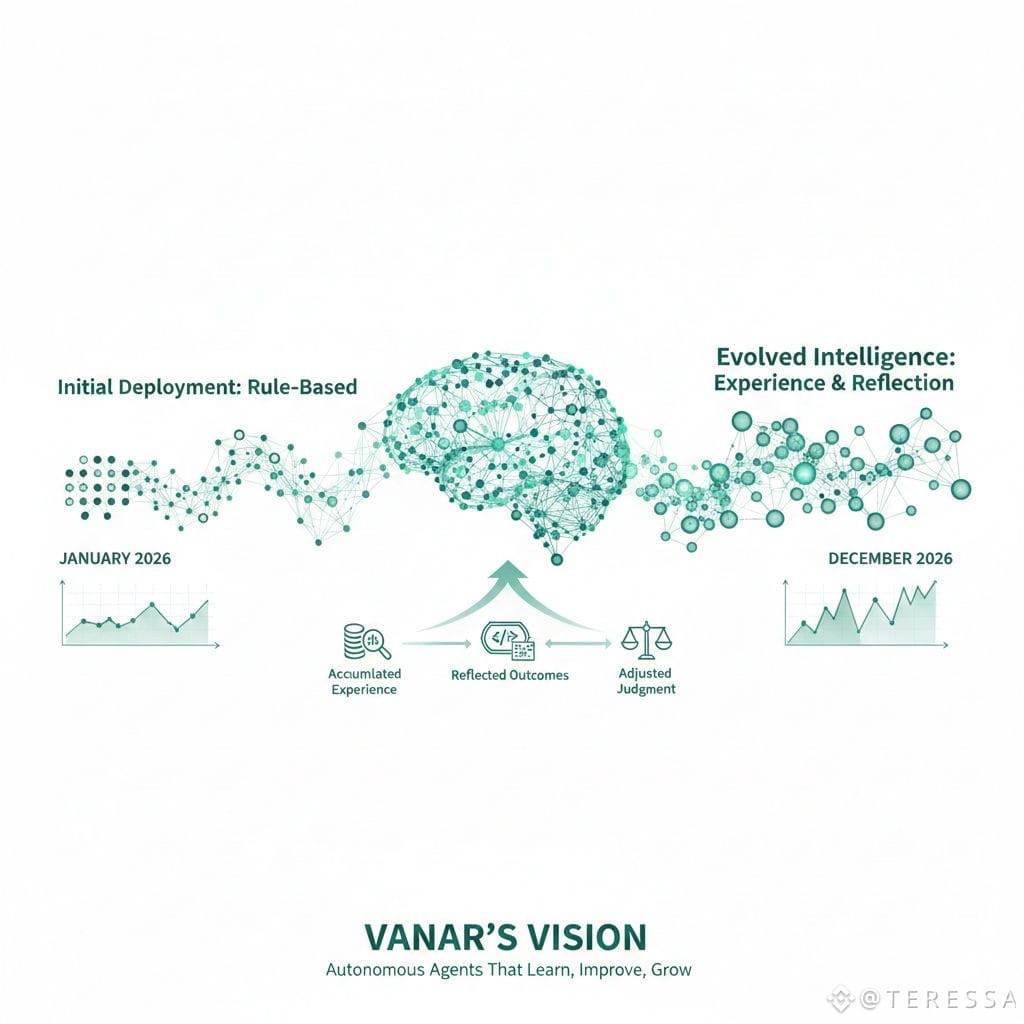

Vanar's vision is of agents that genuinely learn, improve, and grow. An agent deployed to handle financial decisions in January is measurably smarter by December—not because its code changed, but because it accumulated experience, reflected on outcomes, and adjusted its judgment. An agent that processes supply chain decisions becomes increasingly attuned to the specific dynamics of your organization's supply chain, not because it was specially configured, but because it learned.

For organizations tired of AI systems that never get better, that cannot explain themselves, and that become obsolete whenever a new version is released, Vanar's approach offers something genuinely novel: agents that remember, reason about what they remember, improve based on that reasoning, and carry their accumulated wisdom forward indefinitely. The infrastructure for actual machine learning—not just statistical pattern-matching, but genuine learning from experience—finally exists. Agents can actually remember and grow.