A storage system is often judged by what it promises. But it is shaped, quietly, by what it refuses to promise. In an open network, you cannot assume every participant will be kind, competent, or even present. You also cannot assume every user wants to speak the language of protocols. Most people simply want to store something and retrieve it later. Between these two realities, optional infrastructure often appears. It is not the core of a system, but it becomes the part people touch first.

Walrus is a decentralized storage protocol designed for large, unstructured data called blobs. A blob is simply a file or data object that is not stored as rows in a database table. Walrus focuses on storing and reading blobs and proving their availability. It aims to keep content retrievable even if some storage nodes fail or behave maliciously. In distributed systems this possibility is often described as a Byzantine fault. It means a node can be offline, buggy, or dishonest.

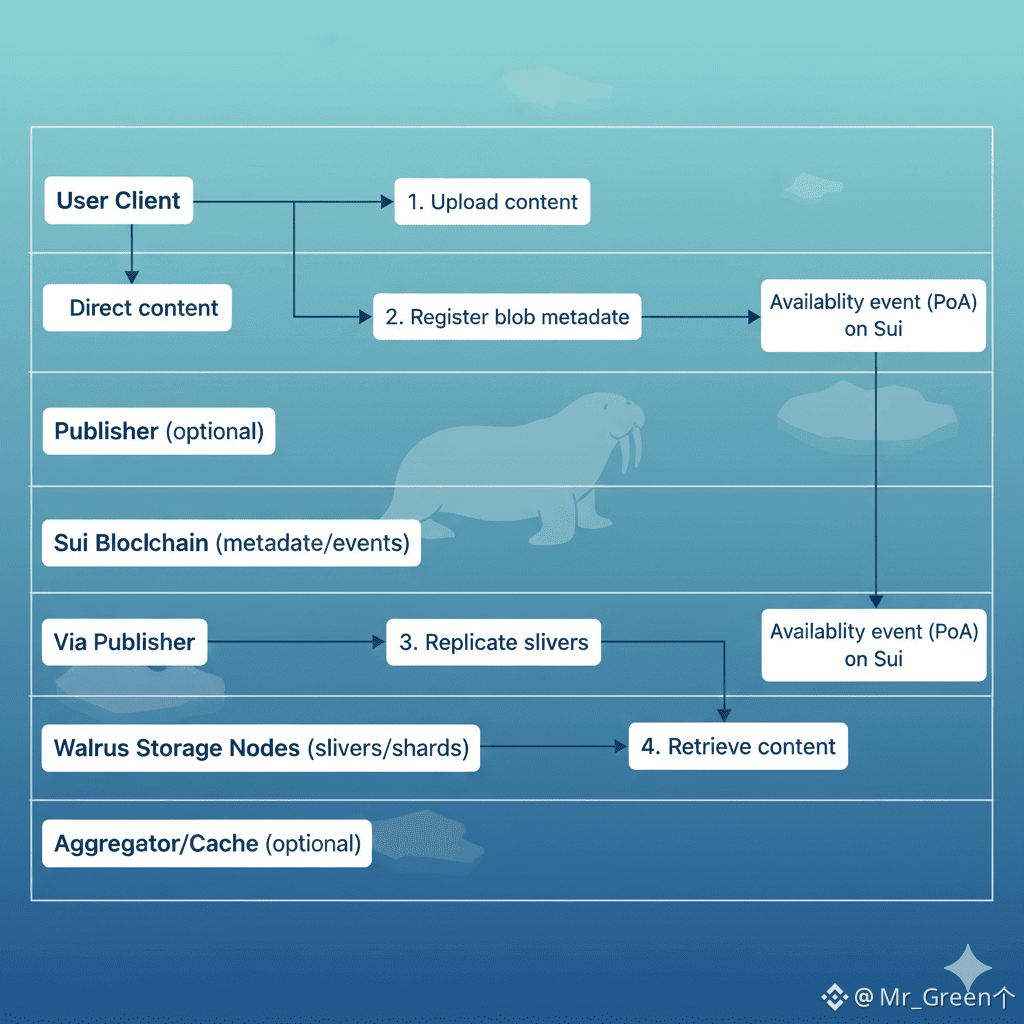

Walrus separates two things that are often tangled. The blob content stays off-chain on Walrus storage nodes. The coordination, payments, and public signals of availability live on the Sui blockchain. Walrus states that metadata is the only blob element exposed to Sui or its validators. This matters because it sets the stage for the optional layer. If content is off-chain, then there must be practical ways for people to upload and read content without turning the blockchain into a file server. If availability is a verifiable claim, then there must be ways to serve data quickly without asking users to trust the server that served it.

Walrus names three optional actors that help with this: aggregators, caches, and publishers. “Optional” here is not a marketing word. It is a security posture. Walrus does not require these actors for correctness. A user can read by reconstructing blobs directly from storage nodes. A user can write by interacting with Sui and storage nodes directly. Optional actors exist because real systems need bridges. They translate between the decentralized storage world and familiar Web2 tools such as HTTP.

An aggregator is a client that reconstructs complete blobs from individual slivers and serves them to users over traditional Web2 technologies like HTTP. The word “sliver” comes from how Walrus stores data. Walrus uses erasure coding, a method that adds redundancy without copying the full blob many times. Erasure coding transforms a blob into many encoded parts. Walrus groups multiple symbols into a sliver and assigns slivers to shards. Storage nodes manage shards during a storage epoch and store the slivers for their assigned shards. When someone wants the blob back, enough slivers can be fetched and the blob can be reconstructed. This is the act an aggregator performs on behalf of a reader. It is not magic. It is reconstruction plus delivery.

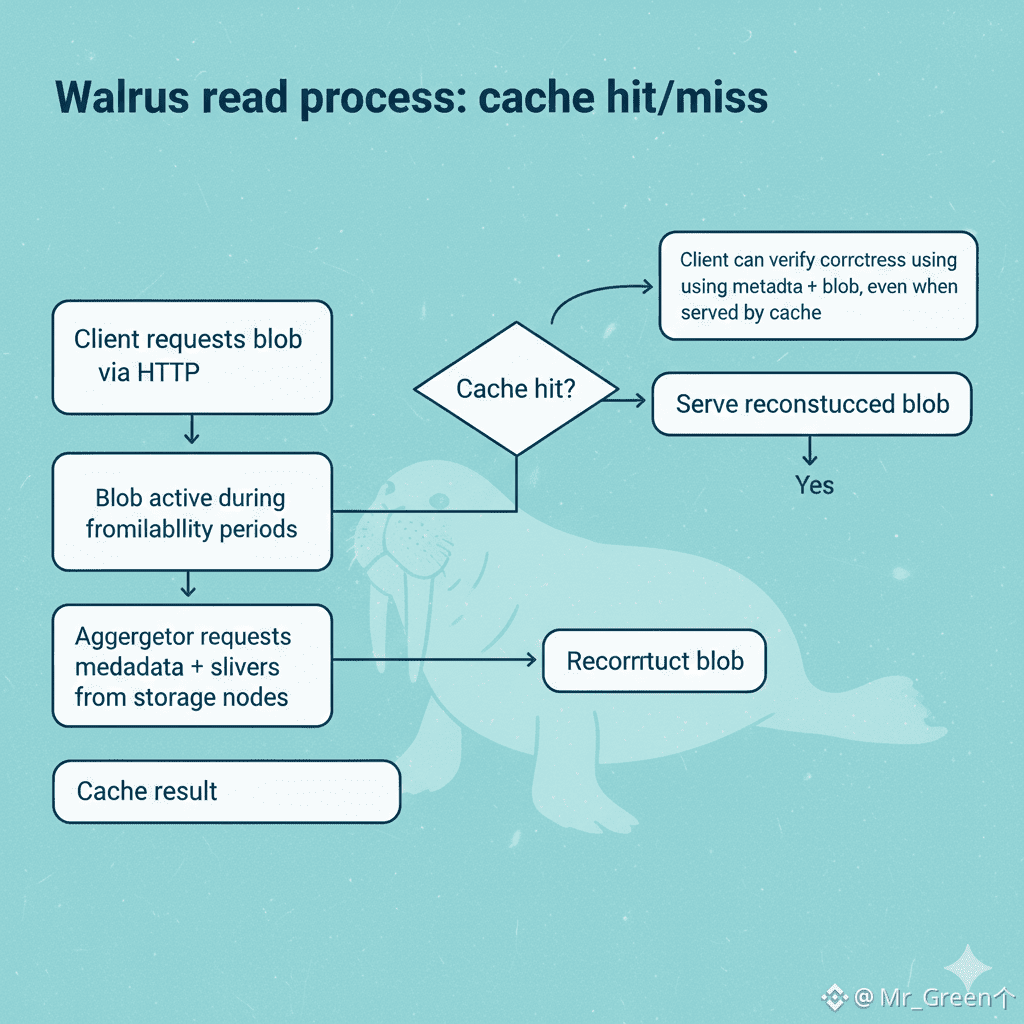

A cache is an aggregator with extra caching functionality. Caches reduce latency and reduce load on storage nodes by keeping reconstructed results around for reuse. Walrus also describes cache infrastructures that can act as CDNs. The key point is not the label. The key point is that the same blob, once reconstructed, can be served many times without repeating the full reconstruction work each time. This can make reads more practical for popular content, while keeping the storage network from being overwhelmed by repeated heavy operations.

A publisher is a client that helps end users store blobs through Web2 technologies while using less bandwidth and offering custom logic. Walrus describes a publisher as a service that can receive a blob over HTTP, encode it into slivers, distribute slivers to storage nodes, collect storage node signatures, aggregate signatures into a certificate, and perform the required on-chain actions. This changes the experience for many users. Instead of needing to run local tools that talk to both Sui and many storage nodes, a user can upload once, in a familiar way, and the publisher can drive the multi-step protocol forward.

It is important that Walrus does not treat these actors as trusted pillars. Walrus explicitly states that aggregators, publishers, and end users are not considered trusted system components, and they might arbitrarily deviate from the protocol. That sentence is easy to read quickly, but it carries a strong design intention. The system is built so that these actors can exist, can be useful, and can even be widespread, without becoming a single point of trust.

This is where Walrus’s verification model matters. Each blob has an associated blob ID that helps authenticate data. Walrus describes computing hashes of sliver representations for each shard, placing them into a Merkle tree, and using the Merkle root as the blob hash. A Merkle tree is a structure that lets many pieces of data be committed under one root hash, while still allowing later verification that individual pieces match the commitment. With this model, a reader can verify that what they received matches what the writer intended, using the authenticated metadata tied to the blob ID. This is why Walrus can say that a client can verify reads from cache infrastructures are correct. The cache can speed up delivery, but correctness does not have to depend on trusting the cache.

The same principle applies to publishers. A publisher can make storage easier, but the user is not required to take the publisher’s word for it. Walrus describes a way for an end user to verify that a publisher performed its duties correctly. The user can check that an event associated with the point of availability exists on-chain. Then the user can either perform a read and see whether Walrus returns the blob, or encode the blob and compare the result to the blob ID in the certificate. This is a practical audit path. It does not rely on the publisher being honest. It relies on publicly observable events and verifiable content commitments.

To see why these optional actors exist, it helps to look at the write path in Walrus. A user first acquires a storage resource on Sui. Storage resources can be owned, split, merged, and transferred. When the user wants to store a blob, the user erasure-codes it and computes its blob ID. The user then updates a storage resource on Sui to register the blob ID, emitting an event that storage nodes listen for. The user sends blob metadata to all storage nodes and sends each sliver to the node managing the corresponding shard. Storage nodes verify slivers against the blob ID and check authorization via the on-chain resource. If correct, they sign statements and return them. The user aggregates enough signatures into an availability certificate and submits it on-chain. When verified, an availability event is emitted. That event marks the point of availability, the moment when Walrus takes responsibility for maintaining availability for the availability period.

A publisher can perform many of these steps on behalf of the user. It can receive the blob through HTTP, do the encoding, handle distribution, gather signatures, submit on-chain actions, and return results. This can reduce bandwidth for the user and simplify the process. But it also introduces a new place where things can go wrong. A publisher might be buggy. It might be overloaded. It might behave dishonestly. Walrus’s stance is that the publisher is helpful, but not trusted. The user can still check what happened by looking for on-chain events and by verifying blob IDs through reconstruction and hashing.

The read path also explains the role of aggregators and caches. Walrus describes reading a blob by first obtaining metadata for the blob ID from any storage node and authenticating it using the blob ID. The reader then requests slivers from storage nodes and waits for enough to respond. Requests can be sent in parallel to ensure low latency. The reader authenticates returned slivers, reconstructs the blob, and decides whether the contents are valid or inconsistent. A cache can sit in the middle and serve reconstructed blobs over HTTP. If the cache does not have the blob, it behaves like an aggregator and performs reconstruction. If the cache has it, it can serve it directly, and the client can still verify correctness.

This makes the optional layer feel less like a “shortcut” and more like a “lens.” It is a way of seeing the same system through interfaces people already know. Walrus states that it supports flexible access through CLI tools, SDKs, and Web2 HTTP technologies. It also states that it is designed to work well with traditional caches and content distribution networks, while ensuring all operations can also be run using local tools to maximize decentralization. That last phrase is important. It implies two futures that can coexist. One future is convenience through shared infrastructure. Another future is independence through local tooling. Walrus tries to keep both possible.

There is also a boundary in what Walrus does not attempt to build. Walrus explicitly says it does not reimplement a CDN that is geo-replicated or has extremely low latency. Instead, it ensures that traditional CDNs are usable and compatible with Walrus caches. This is a pragmatic choice. It accepts that the web already has a performance layer, and it focuses on making that layer compatible with verification. Similarly, Walrus does not reimplement a full smart contracts platform. It relies on Sui smart contracts to manage Walrus resources and processes, including payments, storage epochs, and governance.

If you step back, publishers, aggregators, and caches represent a simple philosophy: do not force every user to become an operator, but do not force every user to trust an operator. Offer services that make the system easier to use, then provide tools to audit them. Keep the core protocol strong enough that optional infrastructure can exist without being a hidden dependency for correctness.

In the end, the optional layer is not just about speed or convenience. It is about giving decentralized storage a human shape. People want HTTP because it is familiar. They want caching because latency is real. They want simplified uploads because complexity is costly. Walrus acknowledges those needs, but it also keeps a disciplined boundary: intermediaries can help, but verification must remain possible. That balance is one of the most practical forms of decentralization.